The Great SARS-CoV-2 Charade: Chapter II

Events between 2015-2020: Creating chimeric viruses that will infect humans

By JOHN LEAKE

Author’s Note: The following is Chapter II in a four-part series about the true origin of SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19 illness. For Background and Context, please see Chapter I. Because of the great deal of time and effort that went into researching this report, I initially published it for paid subscribers only, but this morning a close friend persuaded me that because of its critical importance, there should be no limit placed on its distribution. If you find this report interesting, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. For only $5.00 per month, you can support our ongoing effort to ascertain and report the truth about our confusing world. Thank you for subscribing.

CHAPTER II: Creating Chimeric Viruses That Will Infect Humans

As noted in Chapter I, starting in 2013, UNC Professor Ralph Baric worked with scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) to perform gain-of-function work on Bat SL-CoV-WIV1 and SHCO15 coronaviruses. His collaboration with Ge Xing-Ye and Shi Zhengli began shortly after they (along with Peter Daszak) discovered these two viruses in horseshoe bats in southern China. Xing-Ye, Zhengli, and Daszak published their discovery in Nature magazine in a 2013 paper titled Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. They were very excited about it, because for the first time in history, they found a wild bat coronavirus that would bind with a human ACE2 receptor—a protein (enzyme) on the surface of many cell types.

With this important discovery, Baric commenced work with his Chinese colleagues to fashion these two viruses into two new chimeric viruses that would infect the human respiratory tract. They reported their results in papers published in 2015 and 2016.

1). A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence (published in Nature Medicine)

2). SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence (published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS).

It’s important to understand that a chimeric virus is one that combines genetic material from two or more different viruses. The word comes from the Greek chimera—a mythical monster with a lion's head, a goat's body, and serpent's tail.

They recounted their process for creating the chimeric virus as follows:

In contrast, 7 of 14 ACE2-interaction residues in SHC014 are different from those in SARS-CoV, including all five residues critical for host range. These changes, coupled with the failure of pseudotyped lentiviruses expressing the SHC014 spike to enter cells, suggested that the SHC014 spike is unable to bind human ACE2. However, similar changes in related SARS-CoV strains had been reported to allow ACE2 binding, suggesting that additional functional testing was required for verification. Therefore, we synthesized the SHC014 spike in the context of the replication-competent, mouse-adapted SARS-CoV backbone (we hereafter refer to the chimeric CoV as SHC014-MA15) to maximize the opportunity for pathogenesis and vaccine studies in mice.

It would be hard to find a more perfect description of gain-of-function work. Indeed, as they state in their “Biosafety and biosecurity” section:

Reported studies were initiated after the University of North Carolina Institutional Biosafety Committee approved the experimental protocol. These studies were initiated before the US Government Deliberative Process Research Funding Pause on Selected Gain-of-Function Research Involving Influenza, MERS and SARS Viruses (This paper has been reviewed by the funding agency, the NIH. Continuation of these studies was requested, and this has been approved by the NIH).

In other words, because the project was initially approved before the Pause on GOF research, it was allowed to continue even after the pause was initiated. This is the equivalent of imposing a speed limit in a new urban development on everyone except people who used the road before the speed limit was imposed— that is,“You guys who drove here when it was just a country road may still drive 60 MPH on it, even though it now passes through a newly constructed school zone.”

Shortly after Baric et al. published their first paper in Nature Medicine, they published another paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) titled SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence in which they created another chimeric virus using bat SL-CoV-WIV1, which they called WIV1-MA15.

In the Discussion section, the authors note:

Overall, the results from these studies highlight the utility of a platform that leverages metagenomics findings and reverse genetics to identify prepandemic threats. For SARS-like WIV1-CoV, the data can inform surveillance programs, improve diagnostic reagents, and facilitate effective treatments to mitigate future emergence events. However, building new and chimeric reagents must be carefully weighed against potential gain-of-function (GOF) concerns. Whereas not generally expected to increase pathogenicity, studies that build reagents based on viruses from animal sources cannot exclude the possibility of increased virulence or altered immunogenicity that promote escape from current countermeasures. As such, the potential of a threat, real or perceived, may cause similar exploratory studies to be limited out of an “abundance of caution.” Importantly, the government pause on GOF studies may have already impacted the scope and direction of these studies.

In 2017, Ng and Tan (at the University of Singapore) published a paper titled Understanding bat SARS-like coronaviruses for the preparation of future coronavirus outbreaks — Implications for coronavirus vaccine development in which they recount the important recent discovery of SHCOI4 and the chimeric SHC014-MA15, which demonstrate that bat coronaviruses COULD infect humans on an epidemic scale. The authors therefore emphasize humanity’s need to work on vaccines in order to counter this possible threat.

The 2015, 2016, and 2017 papers reveal the prevailing doctrine in this field of applied research: 1). Find viruses in nature that could evolve to infect humans. 2). Tinker with them in the lab to make them infectious to humans. 3). Create (potentially profitable) vaccines in order to counter the possibility that the infectious virus you just created could eventually, through the natural process of viral mutation and evolution, come about in nature. In the event that it does, you can use your new vaccine to counter it.

Though none of the papers mention the potential military application of this technology, it’s easy to imagine the strategic value of possessing an infectious viral respiratory pathogen AND a vaccine that will protect one’s people from it.

The creation of the chimeric viruses SHC014-MA15 and WIV1-MA15 raises a number of questions:

1). Given that Baric and his Chinese colleagues worked together to create these chimeric viruses, it is logical to infer that they kept samples of them in their labs at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and at the University of North Carolina. Were these chimeric viruses used for additional studies or to challenge SARS coronavirus vaccine candidates?

2). Were additional genetic modifications made to these chimeric viruses—that is, modifications that ultimately resulted in the creation of SARS-CoV-2?

3). Were these chimeric viruses a proof of concept that spawned the creation of additional chimeric viruses? If so, where are they?

4). Was SARS-Cov-2 created at the WIV—using gain-of-function technology and models provided by Dr. Baric—and then simply concealed from international investigators?

5). Have ANY independent investigators compared SHC014-MA15 and WIV1-MA15 to SARS-CoV-2?

In Chapter III of this series, I will show how no serious effort has been made to answer these questions. In February of 2020, Shi Zhengli (Ralph Baric’s principle colleague at the WIV) told Scientific American that when the strange new cases of pneumonia emerged in Wuhan, she compared the SARS-CoV-2 sequence with the genetic sequences of the coronaviruses samples in her lab:

Shi instructed her group to repeat the tests and, at the same time, sent the samples to another facility to sequence the full viral genomes. Meanwhile she frantically went through her own lab’s records from the past few years to check for any mishandling of experimental materials, especially during disposal. Shi breathed a sigh of relief when the results came back: none of the sequences matched those of the viruses her team had sampled from bat caves. “That really took a load off my mind,” she says. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

Mainstream media outlets throughout the West interpreted Shi Zhengli’s statement as settling the matter. She was, it seemed, a perfectly reliable witness who would never conceal anything that could generate historically unprecedented liabilities for herself, her lab, and for her country, and nor would she ever come under duress from state officials to do so. Scientific American also seemed strangely satisfied with her statement that the novel virus matched none of the sequences of “viruses her team had sampled from bat caves.” What about the chimeric viruses she’d created with Ralph Baric five years earlier?

PETER DASZAK’S PROJECT DEFUSE

On 24 March 2018, Peter Daszak submitted a proposal to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, titled Project DEFUSE: Defusing the Threat of Bat-borne Coronaviruses. The proposal sought $14,209,245 from DARPA. The project involved working with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Ralph Baric, and other scientists to create and deploy an aerosolized product for spraying into bat caves in Yunnan Province (south China) in order to inoculate bats and up-regulate their immune systems with additional agents in order to defuse the threat of SARS-CoV viruses that were deemed to pose a risk to human health.

This proposal to stimulate bat colony herd immunity specifically mentioned viruses of special interest:

We have isolated three strains there (WIV1, WIV16 and SHC014) that unlike other SARSr-CoVs, do not contain two deletions in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the spike, have far higher sequence identity to SARS-CoV, use human ACE2 receptor for cell entry, as SARS-CoV does, and replicate efficiently in various animal and human cells, including primary human lung airway cells, similar to epidemic SARS-CoV.

Chimeras (recombinants) with these SARSr-CoV S genes inserted into a SARS-CoV backbone, and synthetically reconstructed full length SHCO14 and WIV1 cause SARS-like illness in humanised mice (mice expressing human ACE2), with clinical signs that are not reduced by SARS-CoV monoclonal antibody therapy or vaccination.

After SARS-CoV-2 was sequenced in 2020, virologists all over the world marveled that part of its genetic code featured inserts for a furin cleavage site—that is, a segment of four amino acids that enables a virus to use furin in the human body as an enzyme to dissolve its coating so that it can release its genetic material to infect cells. On page 13 of the proposal, Daszak wrote:

We will analyze all SARS-CoV gene sequences for appropriately conserved proteolytic cleavage sites in S2 and for the presence of potential furin cleavage sites. SARS-CoV with mismatches in proteolytic cleavage sites can be activated by exogenous trypsin or cathepsin L. Where clear mismatches occur, we will introduce appropriate human specific cleavage sites and evaluate growth potential in Vero cell and HAE cultures. In SARS CoV, we will ablate several of these sites based on pseudotyped particle studies and evaluate the impact of select SARSr-CoVS changes on virus replication and pathogenesis.

Apparently realizing that Daszak was proposing dangerous gain-of-function research and a potentially dangerous inoculation experiment (with unforeseen consequences) on bat colonies, DARPA turned down the grant proposal. About 1.5 years after SARS-CoV-2 emerged, a whistleblower leaked the DEFUSE grant proposal, and researchers all over the world noticed statement on page 13 about introducing “appropriate human specific cleavage sites and evaluate growth potential in Vero cell and HAE cultures.”

When Peter Daszak was asked about this, he replied that it was a moot point, given that DARPA had turned down the proposal. Nevertheless, given the history of the project’s participants (Ralph Baric and his WIV colleagues), suspicion was raised that they had already performed much of the work they were proposing and seeking money for. As Rutgers University Professor Richard Ebright pointed out:

In the molecular life sciences, it is the norm to begin, and often make substantial progress on, new lines of research before seeking and obtaining funding for the research,” said Ebright. It would be unusual for a research group with multiple current lines of funding not to have started a new line of research before obtaining funding for it, and it would be almost unheard of for a group with multiple current lines of support not to proceed with a new line of research simply because an application for an additional line of funding application was not approved.

THE RETURN OF THE FRENCH CONNECTION

In a May 21, 2020 investigative report, the French news magazine MediaPart recounted:

The maximum-level biosafety laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology … was built with the help of French experts and under the guidance of French billionaire businessman Alain Mérieux, despite strong objections by health and defence officials in Paris. Since the laboratory's inauguration by prime minister Bernard Cazeneuve in 2017, however, France has had no supervisory role in the running of the facility and planned cooperation between French researchers and the laboratory has come to a grinding halt.

The Franco-Chinese Agreement to build the lab was executed in 2004 and construction was completed in 2015. Precisely as some French defense officials had warned, the Chinese did NOT abide by the Agreement’s provision for French scientists to remain in supervisory positions at the lab. When the lab opened for operations, it was entirely in the hands of Chinese administrators.

Just before the lab opened, Rutgers University Professor Richard Ebright issued a stark warning to the world that it was not properly equipped and staffed to contain such dangerous pathogens. Shortly after the lab opened (on January 19, 2018) a State Department official posted at the US Embassy in Beijing sent a cable to Washington, warning that the “new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory.”

The new BSL-4 lab at the WIV is linked by a walkway to the older, BSL-3 laboratory, where Shi Zhengli worked when she collaborated with Ralph Baric in creating SHC014-MA15 and WIV1-MA15. Here it is important to remember that it was her team (along with Peter Daszak) that collected the original SHCO14 and WIV1 viruses from horseshoe bats in southern China. It’s clear from their 2015 paper that both the BSL-3 lab in Wuhan and Ralph Baric’s BSL-3 lab at UNC Chapel Hill worked on the viruses.

SARS-CoV is a select agent. All work for these studies was performed with approved standard operating procedures (SOPs) and safety conditions for SARS-CoV, MERs-CoV and other related CoVs. Our institutional CoV BSL3 facilities have been designed to conform to the safety requirements that are recommended in the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the NIH.

Regarding who supported the creation of the SARS-CoV virus, the authors write in their Acknowledgements:

Research in this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Disease and the National Institute of Aging of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and by USAID-EPT-PREDICT funding from EcoHealth Alliance.

With joint funding from the NIAID and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and with the original, natural viruses provided by Shi Zhengli’s team at the WIV, it’s a reasonable inference that BOTH labs kept samples of the chimeric viruses that they created together. What did Ralph Baric do with his samples between the years 2015 and 2020?

MODERNA’S CURIOUS 2016 PATENT

On February 21, 2022, Frontiers in Virology published a report titled MSH3 Homology and Potential Recombination Link to SARS-CoV-2 Furin Cleavage Site. The Furin Cleavage Site is the component of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that enables the virus to dock onto human lung epithelial cells, thereby initiating the viral infection and replication process. It is an important feature of SARS-CoV-2 that made it infectious to humans. Examining the genetic code of this part of the spike protein, the authors noted that part of the sequence was a perfect match to a genetic sequence patented in 2016 by Bancel S. et al. in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and MSH3

A peculiar feature of the nucleotide sequence encoding the PRRA furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 S protein is its two consecutive CGG codons. This arginine codon is rare in coronaviruses: relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of CGG in pangolin CoV is 0, in bat CoV 0.08, in SARS-CoV 0.19, in MERS-CoV 0.25, and in SARS-CoV-2 0.299 (8).

A BLAST search for the 12-nucleotide insertion led us to a 100% reverse match in a proprietary sequence (SEQ ID11652, nt 2751-2733) found in the US patent 9,587,003 filed on Feb. 4, 2016.

On the question of whether this perfect match could be mere coincidence, the authors noted:

Conventional biostatistical analysis indicates that the probability of this sequence randomly being present in a 30,000-nucleotide viral genome is 3.21×10^-11 [approximately 1 in 3 trillion].

The Daily Mail reported the Frontiers in Virology report, which prompted Fox News’s Maria Bartiromo to question Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel about his 2016 gene patent. His cool brushoff was suggestive of a man unconcerned about media queries. Why should he be? When it comes to the Bio-Pharmaceutical Complex, the US mainstream media rarely asks tough questions, and never pursues serious inquiry.

Inquisitive viewers might have wondered: Who is Stéphane Bancel, and why is a French national heading a Cambridge, Massachusetts biotech that was originally funded by a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) grant?

As I recounted in Chapter I of this series, Bancel was the CEO of BioMérieux in the years 2007-11, when the French in vitro diagnostics company was in the early stages of planning and building a new BSL-4 lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. In 2011, Bancel left his plum position at bioMérieux to become CEO of Moderna. At the time it seemed like a Quixotic decision, because the company was just a concept, and not a going concern.

However, two years later, in 2013—the same year that Ralph Baric started collaborating with colleagues at the Wuhan Institute of Virology to perform gain-of-function work on bat coronaviruses, Moderna drew interest from DARPA, which awarded it a $25 million grant to develop messenger mRNA therapeutics.

Sometime around 2015—the same year in which Ralph Baric published his initial paper on the chimeric virus he created with his collaborators at the WIV with research funding provided by the NIAID—Moderna also began collaborating with the the NIAID to develop mRNA vaccines against SARS and MERS coronaviruses.

In the year 2016, Bancel et al. filed for their patent of the genetic sequence for part of the coronavirus spike protein furin cleavage site—the same genetic sequence that was, four years later, found in the furin cleavage site of SARS-CoV-2.

Bancel’s decision to leave bioMerieux to lead Moderna worked out well. On March 16, 2020—just five days after the WHO declared SARS-CoV-2 to be the causative agent of a worldwide pandemic, NIAID issued a press release stating it had commenced human trials of its mRNA-1273 vaccine.

mRNA-1273 was developed by NIAID scientists and their collaborators at the biotechnology company Moderna, Inc., based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) supported the manufacturing of the vaccine candidate for the Phase 1 clinical trial.

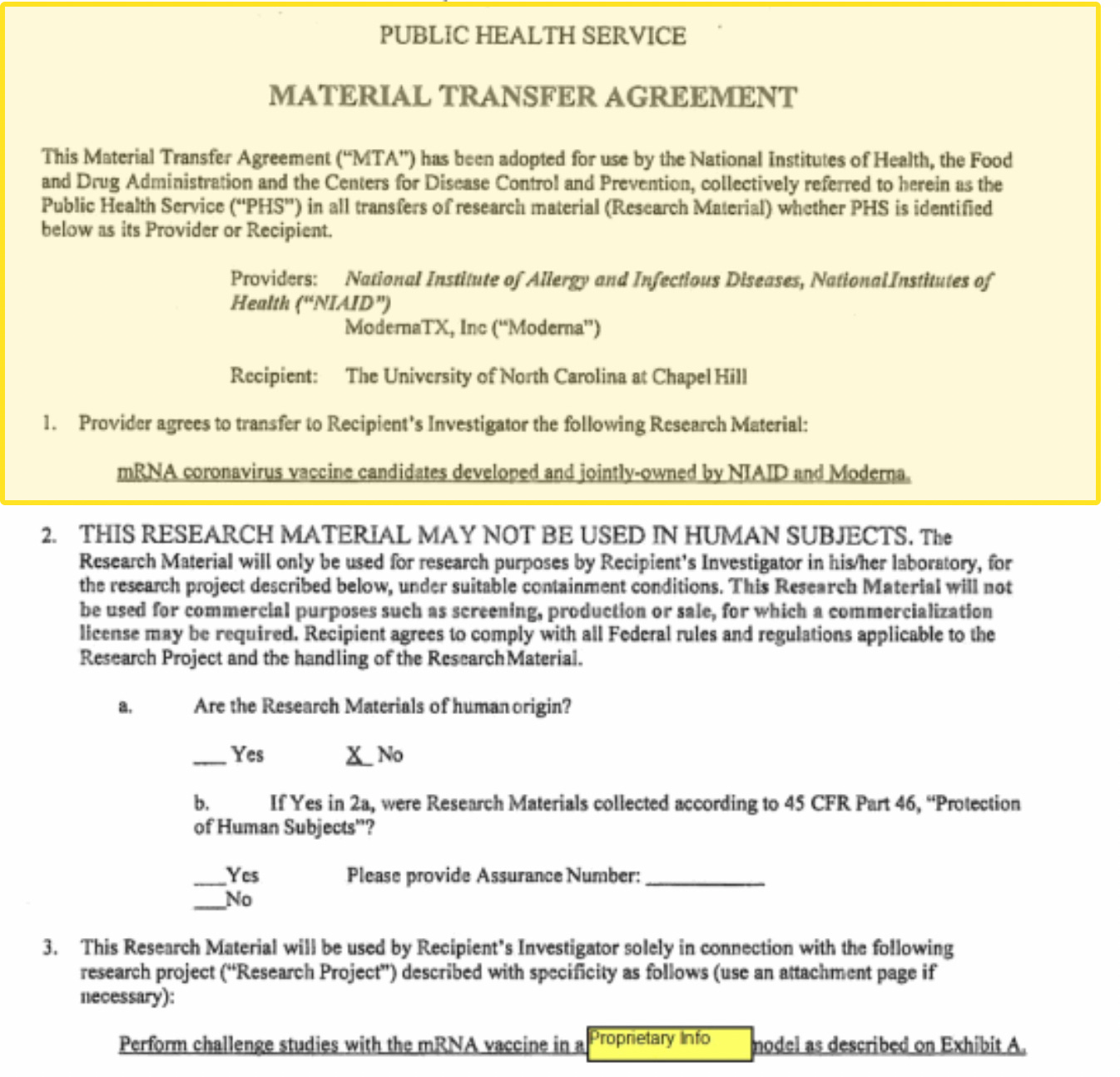

A conspicuous feature of the development timeline for mRNA-1273 is a MATERIAL TRANSFER AGREEMENT (see pages 105-107) from NIAID/Moderna (“Provider”) to Ralph Baric (“Research Recipient”). The Agreement specifies the transfer of “mRNA coronavirus vaccine candidates developed and jointly owned by NIAID and Moderna” to Dr. Baric “to perform challenge studies with the mRNA vaccine.”

The Agreement is signed by Ralph Baric on December 12, 2019—19 days before the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission informed the WHO China Country Office of “cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China on December 31, 2019, and 24 days before the genome of SARS-CoV-2 was published on January 5, 2020.

Why did NIAID and Moderna believe that Dr. Baric was equipped to challenge their “mRNA coronavirus vaccine candidates”? Did they provide Dr. Baric with the coronaviruses to be used for his challenge studies, or did he already possess them in his laboratory?

This collaboration, which came about on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, proved to be very profitable for NIAID and Moderna. Less than a year later—with the United States government relentlessly pushing Moderna’s mRNA and Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccines as the ONLY solution to the COVID-19 pandemic, Moderna’s CEO, Stephane Bancel became a billionaire.

Dear Readers,

Many thanks for your kind and supportive words and your critical feedback. Though time does not allow us to respond to each of your comments, we read and appreciate all of them. I am especially encouraged by the feedback of critical readers who have some training in the scientific fields we are researching and writing about. Please share this post with your colleagues and let them know we welcome their feedback as well. Best regards, John Leake

excellent article, thanks for providing it for free